But with Godzilla you’re in a distinctly Japanese theme. In fact, when you think of Japan, probably one of the first images to come to mind is Godzilla. Which is awesome. A dragon/dinosaur that has atomic breath sure beats a bald eagle in my book – I think the U.S. is due for an upgrade. Sure, there’s the stomping and the sheer thrill of destruction that guys delight in, the same way I used to videotape my toy Godzilla rampaging through Micro Machine playsets. But as anyone who’s bothered to look past the campiness knows, the core of the franchise is about a kind of stoic, national fatalism in the light of giant primeval monsters and an environmental apocalypse.

Remember that originally Godzilla symbolized the terror of the Atomic Bomb, or more generally the atomic weapons of the American military. It was a cinematic way to deal with the widespread fear, anxiety, and paranoia that blanketed the country. In the end, the only thing that can defeat Godzilla is Dr. Serizawa’s Oxygen Destroyer and his own kamikaze sacrifice so the awesome device can never be used again – quite the opposite of Manhattan Project scientists developing the Bomb for destructive purposes.

In later installments, as some of the aftermath of the War and memories of air raids and firebombings began to fade, the series became geared more towards cheesy entertainment for children and the Big G often became an unintentional defender of Japan from other monsters, with citizens grateful for his intervention.

The whole Godzilla as divine punishment for nuclear testing angle was tempered by the bizarre angle that Godzilla is possessed by the restless dead of World War II and attacks Japan as divine punishment for neglecting to honor the fallen soldiers and their sacrifices, and to a greater extent the victims of Japanese aggression (much like Marvel’s Everwraith character). In Godzilla, Mothra and King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack (2001), the new generation of folks have consigned the idea of Godzilla to fairy tales and need to be reminded of the horrors of war. To me, it seems like the two groups of dead would cancel each other out, but hey.

Wait, does that mean the more Godzilla kills, the more souls get added to fuel his power? Is this all a non-too-subtle play to get people should pay respects at Yasukuni Shrine and have Shinto exorcisms? Or else combine franchises and use Space Battleship Yamato to fend off Godzilla? One can only hope.

The idea of Godzilla shifted and evolved along a blurry spectrum from the A-Bomb and U.S. forces to frivolous fun and pop culture icon, one of Japan’s best-known exports and therefore, curiously, a symbol of Japan itself. Though U.S.-Japan relations over the early years account for most of the fear-familiarity-domestication-absorption-identification continuum, no matter how friendly movie-goers got with him, Godzilla remained the dread of existential angst in a post-nuclear world. He is at once unspeakable terror and mindless entertainment phenomenon next to Hello Kitty.

Of his many incarnations, Godzilla was originally planned to be a giant octopus, a nightmarish, anthropoid creature that makes many of us Westerners queasy just thinking about it. Even this would have been favorable to Roland Emmerich’s insultingly puerile 1998 version where baby Godzillas can be slowed down with basketballs and gumballs (it’s kind of the equivalent of what Joel Schumacher to Batman). If you’re just dying to see what a giant rampaging octopus would look like, Ray Harryhausen’s It Came from Beneath the Sea (1955) came out the year after the first Godzilla movie.

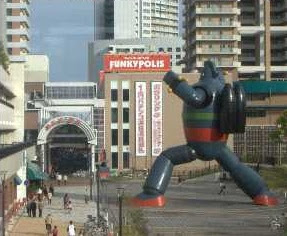

To be honest, aside from the first installment and a couple others from the various Showa, Heisei, and Millennium series, it can be difficult to find any solid stories with cohesive plot lines. Nevertheless, Godzilla became so popular that it spawned innumerable other monster movies, often with giant robots brought in to repel the foreign menace until it was almost a parody of a parody. For many people, this basically sums up Japanese pop culture.

And it’s not like America didn’t have its craze of 1950s alien invasion movies reflecting Cold War fears of body-snatching Communist and radioactive mutants.1 And if you’re tempted to think Japan has some fixation on giant monsters or an inferiority complex to the rest of the world, in reality everyone is fascinated by immensity. Overwhelming size, whether it’s a mountain peak, a towering skyscraper, a goliath of a man like an imposing demi-god, or just a rampaging dinosaur, is a sight of wonder, of the sublime. In fact, it was the U.S. that started the sci-fi/fantasy subgenre in the first place with King Kong and The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (and the re-release of King Kong), which were direct influences on Godzilla.

Consider a cursory list of our films with Them!, Attack of the 50-Foot Woman, Jaws and its sequels, Clash of the Titans (drawing on our ancient Greek myths), Ghostbusters, Ghostbusters II (with the freakin’ Statue of Liberty brought to life to help fight the negative attitude of New Yorkers), Jurassic Park and its sequels, and the remake of King Kong. More recently, Cloverfield was directly inspired by Godzilla, Clash of the Titans received a remake and a sequel in this year’s Wrath of the Titans. It won’t be long before giant robots and giant robots fight again in Guillermo del Toro’s Pacific Rim (2013), proving giant monster movies are still alive and well in the West. America is up to its neck in homegrown monster movies.

Japan at the Crossroads

But the difference is that we were watching stories that were to mirror the unfolding conflict. We had a flesh-and-blood enemy in mind. Japan didn’t have a Cold War to fight. It was a country of pacifists.

|

| Pacifists have a lot of free time and money... |

|

| To build some very peaceful giant robots... |

|

| With peaceful glowy eyes. |

Godzilla is a kind of divine punishment for their hubris of aggression (“our” nuclear bombs woke him up; this is the price we must pay). If you recall, it was often the scientists more than the generals or Prime Ministers who called the shots in the early Godzilla movies. There’s a subtle passivity to such affairs that I would argue carries over from the lack of closure and catharsis following the war2.

Even in Godzilla: Tokyo S.O.S., we have the dilemma where Mechagodzilla “cries” because it doesn’t want to fight, but to sleep peacefully. In the end, Mechagodzilla rebels against its human pilot and sacrifices itself in a kamikaze-strike to bury Godzilla. I kind of wish they had just sold Mechagodzilla to the Americans. We would have reprogrammed it and had no problem keeping it around as another weapon in our arsenal in case King Kong ever returned. In Godzilla: Final Wars, Kazama does the same needless kamikaze attack to take down a shield generator. In fact, Mothra does this on a regular basis. The Japanese seem to have a hard time distinguishing between sacrifice and suicide. There seems to be some link between pacifism and kamikaze strikes.

Pacifism as an all-or-nothing ideology is ultimately absurd and unrealistic and suicidal. War is such a complicated issue; trying to over-simplify it doesn’t help. For the record, America’s superheroes can be just as pathetic about war and nuclear weapons. Not to be outdone by Japanese exclaiming about Godzilla, “We deserve this!” (Really? Shouldn’t Godzilla be attacking America according to that logic?), Superman tackles the problem of nuclear weapons head-on (literally) in Superman IV: The Quest for Peace. The story stretches “patriotic pacifism” to new levels of silliness as Superman fights Nuclear Man (I know, right?!):

Nuclear Man (yes, Nuclear Man!): Where is the woman?

Superman: Give it up, you'll never find her.

Nuclear Man: If you will not tell me, I will hurt people!

[Nuclear Man causes general mayhem]

Superman: Stop! Don't do it! The people!

On the worldview level, Japan’s defining opponent as symbolized by Godzilla was not some empowering foil like Soviet Russia, but a zeitgeist, the existential plight of living in a post-nuclear world without a coherent internal vision. The Emperor had been dethroned. Their version of Manifest Destiny (Yamato-damashii, similar to being a Chosen People, das Herrenvolk) was in tatters. State Shinto was forcibly expunged by the Occupation, just as the power structures of Buddhism had been previously displaced by State Shinto.

There was a gaping spiritual vacuum, a double-edged sword that could prove to be either a great danger or a great opportunity. The danger was that it might let open the door to Communist influence, which MacArthur (with Truman’s O.K.) strove mightily to prevent by filling the void with the dual influences of democracy and Christianity. “Democracy and Christianity have much in common,” MacArthur said, “as the practice of the former is impossible without giving faithful service to the fundamental concepts underlying the latter.”

For democracy, a whole new Constitution was given. For Christianity, MacArthur issued a call for 1,000 missionaries (sometimes inflated by other reports to be 2,000 or even 10,000) and 10 million Bibles.

|

| Apostle of Peace, who will land evangelistic shock-troops right behind your pretty political borders, Truman be darned |

I have to confess though that viewing Christianity in such an almost pragmatic or Realpolitik way seems to miss the whole point of the way of Christ. I think he wrongly connected the implications of Christianity (Christendom?) and individual dignity with democracy. By extension, one might wonder if that meant there was no true Christianity among the kingdoms of the world before the so-called Enlightenment in 1700s Europe. It seems to me that one could replace “Christianity” with “American values” and you have a picture of what he meant.

There is often told the anecdote that when Emperor Hirohito was granted a meeting with General MacArthur, he effectively prostrated himself before the general, saying, “I come before you to offer myself to the judgment of the powers you represent, as one to bear sole responsibility for every political and military decision made and action taken by my people in the conduct of the war.” The emperor, the story goes, went on to say that should MacArthur give the order, he and all his people would become Christians.

MacArthur, probably with pipe in mouth and a pensive faraway look, mulled it over before deciding that no, such a politicized top-down approach basically ruined Christianity with Constantine and furthermore he “felt it wrong to impose any religion on a people.” At least that’s what he told Billy Graham and other church leaders.

The truth is, the only record we have of this incident is from MacArthur himself – the interpreter had a different account – and historians are inclined to believe any such confession by the Emperor would have been much more of a general statement of regret rather than admission of personal guilt. (Another interesting story that the Empress Dowager reportedly said, “What this country needs now is Christianity.”)3

Strangely enough, the real dilemma for the Occupation in weighing the idea of a Christian Emperor was deciding the denomination: would the divine descendant of the Sun Goddess accept the Pope as head, or, if he became Anglican, would he submit to the monarch of England? I guess no one suggested he follow the way of Uchimura’s No-Church movement.

Years later, his assessment seems to have tempered, saying, “Japan would not be Christianized in any conceivable period of time, that pride of race, if nothing else, would prevent most Japanese from doing so.”4

In the end, he was quite successful in stymieing the advance of Communism and promulgating democratic values. But despite his efforts to get the gospel out to the people, there was no great revival of Christianity as in the days of Xavier, 500 years back, when 20% of the population in some sense identified with Catholicism. (As for the times of Nestorian Christianity, any such data has been lost to history. At any rate it likely pre-dated the arrival of Buddhism).

In short, after the war Japan did not learn from our spiritual values, but only our materialism and consumerism. It did not take the best from its conqueror, but the worst, soaking it up like a sponge. And for that America is largely to blame. The spiritual vacuum was left to be filled by secular humanism, which itself is another void that spurred on the monumental rise of the New Religions (read: crazy crackpot cults).

And yet, Japan couldn’t help but feel some spiritual influence from its benefactor. In Mothra (1961), one finds the moth blatantly adopting cross imagery and church bells of savior Christianity over and against villainous Western capitalism typified by Clark Nelson. Eiji Tsuburaya, who was the co-creator and special effects man for Godzilla and Mothra and creator of Ultraman, was himself Catholic. If you tilt your head just so, when Ultraman summons his Specium Beam it looks a bit like he’s making the sign of the cross. For that matter, you even have the cartoon character Anpan Man (Think “Bread Man”) who is implicitly a symbol of Christ.

|

| Ack - Tsuburaya must be rolling over in his urn |

In a nation that is paralyzed with fear when it comes to interpersonal confrontation and avoiding conflict resolution, there is an epidemic of taboo issues such as teenage prostitution, incest, shut-ins (hikikomori) numbering in the millions, “parasite singles”, “Freeters”, “NEETs”, “herbivorous” Fuyuhiko-type single men who are afraid of women, bullying, and biker gangs that roam the streets with impunity (though their numbers are insignificantly small).

I would speak to debts and deficits, but such figures can be looked up and America has all of that and more. As of 2012, there have been seven prime ministers in seven years, resigning in defeat one after another. And, perhaps worst of all, are the absentee workaholic fathers whose negligence spells certain doom for the next generation. “Fatherlessness” is the usual term for this, but I like how my Korean student put it best: “Father-emptiness.” They may never engage their kids, but they’ll work themselves to death for their companies (karōshi). By default, by abdicating their roles in the family, society reverts to a matriarchy.

Parents admit to being clueless when it comes to raising kids. Ostensibly due to a desire for “peace at all costs”, more often than not they let their emotionally-stunted children call the shots, whining, screaming at, and punching their parents to get their way. You might call things topsy-turvy, soft parenting, or co-dependency. No matter the terms, their world is on a slippery slope of losing social cohesion to the point of borderline anarchy.

Mutants and Mystery Men in the American Mythos

In the seventies and eighties, America went through a similar post-apocalyptic phase as it lost its moral center following the Sexual Revolution of the Sixties. The gritty Dirty Harry, Death Wish, Robocop, Escape from New York, and Mad Max movies personified our desires to wrest back control of the world from amoral punks and delinquents. Clint Eastwood’s The Man With No Name bounty hunter character, who came from Kurosawa’s Yojimbo is of the same type.

They weren’t completely new genres though. The pioneer, the cowboy, the noir detective, the costumed superhero, and the astronaut (or futuristic machine-man) are for the most part homegrown on American soil. Our earlier folk heroes like Paul Bunyan, Pecos Bill, and Davy Crockett were poster-kids for frontier expansion. Dirty Harry was merely one part cowboy and one part detective. Robocop, cowboy, detective, and machine. Mad Max (though Australian), cowboy and pioneer. Add in astronaut and you get the space-cowboy (insert President Reagan joke), like Japan’s own intrepid bounty hunter, Spike Spiegel of Cowboy Bebop. Interestingly, Cowboy Bebop is one of the most popular anime in America, but is largely unknown or neglected in Japan, flooded as the market is with other series. With comics, the same could be said of Stan Sakai’s Zatoichi-like Usagi Yojimbo, which garners some awards and recognition State-side, but not nearly enough, and nothing at all from Japan.

In the American mythos today, superheroes reign supreme as the dominant genre. Marvel has recently been enjoying great success in transferring its characters to the big screen. For every bleak UK-based Watchmen - a great Cold War story with a superhero that’s a living nuke - there’s a plethora of made-in-the-USA, industrial-capitalist Iron Mans and liberty-defending republican Captain Americas. On the whole, American comics have always been essentially optimistic.

The costumed adventurers were basically born out of two-fisted vigilante pulps, like Doc Samson and The Shadow, with a dash of Greco-Roman demi-gods thrown in (see Leading Justice to Victory). Superman (1938) was basically the first and final summation of the figure, and he is also, more than any other hero, a thoroughly inspirational messianic figure drawn from America’s Judeo-Christian roots. In those days the covers pictured organized crime, alien menaces, and fascism. They weren’t just escapist funny books for kids. In the darkest days of WWII, soldiers were carrying Captain America comics in their helmets as they were storming the beaches of Normandy.

Coming out of the Golden Age of the ‘50s, our irradiated heroes of the early 60s were as forward-looking as the NASA space program or the Second Coming. With mutants like the X-Men we could channel our nuclear angst into harmless teenage fantasy. Instead of fearing them as freaks and monsters, we had a new and improved species of man. America was coming of age as a superpower. According to the superhero genre, the Age of the Atom was just some pubescent blemishes to push past. It didn’t occur to anyone to conjure up anything so foreboding and chaotic as Godzilla. (No, Fin Fang Foom doesn't count).

Meanwhile, the vicissitudes of Japanese history, especially as it was still reeling from its greatest catastrophe lent, shall we say, a more dire view of nuclear-powered specimens. Even if America faced a similar fictional threat the way Godzilla symbolized the A-Bomb, as it did with the gamma-irradiated rage-monster the Hulk, we are given more of a sympathetic Byronic hero than a country-decimating inferno. Our Dr. Jekyll/Mr. Hyde version of Godzilla was sometimes misunderstood, but he was never a villain. In fact, characters seemed to be jumping in front of each other to do more gamma ray experimentation. It was like the steroid of choice for the varsity team.

Consider the minor chords to the seminal stories of Japan. The Forty-Seven Ronin is a defeatist tale. Sure we have the great tragedies of Shakespeare, of Hamlet or King Lear, but Hamlet and Lear are not the triumphant, culture-shaping hero stories of Britain – Robin Hood and King Arthur are. Just as Superman and Captain America are to us. What was Cap’s hibernation in the ice after WWII but a temporary visit to Avalon, from whence he would come again on that day that his country needed him the most? (Which apparently was in 1963 when Loki attacked in Avengers #1.

At any rate there had to be a new guiding mythos for Neo-Tokyo. Japan needs something more substantial and inspiring than the cartoonish or nihilistic fare that’s fills most anime. In the end, the new messiah they constructed was technology, specifically mecha like Tetsujin 28-go (1956) and Mazinger Z (1972): Gundams with the firepower to finally smack down Godzilla.

So that’s how it played out on the opposite sides of the Bomb. Our mutants are good and robots are bad. Japan’s robots are good and mutants are bad.

Stuck in the Uncanny Valley

There’s just one problem with that. I hate to break it to you, but when it comes to inspirational hero figures, giant robots are just surrogates, cheap substitutes for real saviors. People can’t relate to them the same way as flesh-and-blood characters.

The sad truth is Japan approaches the world by proxy, either with robots or cartoons as the projection of Japanese industrial might, stoic manner, emotionless compliance. Robots and cartoons can be dubbed or subbed rather easily. Actual people have to learn the English language and this something Japan hasn’t bothered to do yet. As Styx put it, “I'm not a hero, I'm not a saviour... I am the modern man, who hides behind a mask.” Yeah, thanks a lot, Mr. Roboto… for choking out the development of real heroes.

Look no further than how the recent blue-blooded Avengers movie (like The Incredibles) dealt with real themes and inter-personal conflict in an entertaining way. The Avengers are everything Voltron lacks. They are a real team forged through conflict. Together they are more than the sum of their parts, but individually they carry their own comic titles.

|

| OK, Avengers, just keep those ninjas off of me - that giant personification of existential angst is mine. |

|

| We can't form Mega-Avengerzoidasaurus without Iron Man - he was supposed to be the chest piece! |

|

| Odin's beard, why doth the creature's fins glow like that... |

I would like to examine just how the Iron Giant surpassed and subverted the best the Japanese giant robot genre had to offer. Much like in the original Godzilla story, we are confronted with an ominous postwar ideological backdrop. In the 1950s, America’s greatest fear was the Red Scare and all that went with it: Sputnik, brainwashing propaganda, alien invasion, and atomic holocaust. All of these are personified in one mecha-inspired giant nameless robot.

Similar to the Godzilla movies, it’s also something of an anti-war flick when one of the heroes being a beatnik pacifist, sporting a ying-yang robe, makes a sly reference to Godzilla, referring to expresso as coffee-zilla.) But unlike the novel it was based on, which is more of the absurd world peace sort of plot with contests of strength against dragons from outer space (sound familiar?), the film stands as a powerful real-world case for de-escalation. If Japan was serious about being respected on the world stage it should make it required studies, just as The Incredibles should be standard viewing to learn how to be a good husband and father.

The Iron Giant goes for realism. If a giant killer robot came to Earth, especially during the Cold War, we’d start shooting pretty quickly. But here the invasion of the Other theme is turned on its head and it looks like peaceful co-existence is possible. After all, Superman is a super-strong foreigner who protects us (Superman actor Dean Cain, incidentally, is part Japanese). Terminator 2 did the same. There’s a key scene where our protagonist, a little boy named Hogarth, teaches his new pet/friend giant robot to always use his otherworldly powers for good, pointing to a Superman comic. The self-sacrifice values of Superman then becomes the moral center for the robot to save the day, instead of destroying it. Unfortunately he still resorts to a kamikaze-type attack, so maybe some things never change.

|

| Now to defeat the evil Dr. Gun |

A Dearth of Good Hero-Stories: The Fallout

Destruction looms large in Japanese giant monster movies (daikaiju) because it also brings to mind the olden days, a pre-war Japan that is no more. Sure it was backward and autocratic before the Americans came in with the gospel of democracy (I say that only half-jokingly), but nostalgia is nostalgia. We still with some fondness remember Rome with all its decadence and the Old South despite the prejudice (I speak as a proud Southerner).

But this isn’t to say that daikaiju are merely disaster movies or as masochistic as I once thought – but it’s their history. Such exigencies as earthquakes, typhoons, and landslides are a part of daily life over there, and at least with Godzilla that chaos can be personified, giving people a target, something tangible to strike, a rallying point for a demoralized military. After Article 9, what else is a Self-Defense Force to do?

|

| So that's what happened to the GDP |

Films like Akira on the other hand are another duck entirely. The anomie in the anime of not only the cyberpunk tradition, but the landscape of Japanese literature of the past fifty years, is quite disturbing in its schadenfreude. Think Akira and Tetsuo as the free-wheelin’ A-Bomb and H-Bomb. Without a moral center, we’re left with masochistic stories that are unable to give catharsis or closure. I have nothing against post-apocalyptic dystopias. Some of my favorite stories are of that genre. I even wrote a novel set in that sort of world. But the point is that it allows a stark focus on humanity scaled-down and simplified to its bare roots and iron muscle. It took Western civilization centuries to recover from the collapse of Rome and cobble together the Holy Roman Empire from its ruins.

Early on, seminal blood-stained Dark Age heroes like a Beowulf here and there emerge (think Momotaro with a beard, hopped up on mead). But once European society got consolidated into sizeable kingdoms again, we could see legendary figures, like Charlemagne and El Cid and King Arthur and Robin Hood, come forth. Earlier still, the myths of Greece, born out of their own Dark Age has given us countless stories and helped mold the epics of Western literature and culture. Alongside of that you have the epic stories and heroes of the Bible, which has the added bonus of providing an absolute moral center. Odysseus and the Polyphemus the Cyclops is a story for the ages; David and Goliath is for eternity.

I would posit that Japan has no such comparable foundational myth, either from the fertile black soil of their own Dark Ages or among their religious stories. Their Shinto “origin story” if you will, while fun to read, is essentially insular and is difficult to mesh with any kind of character-shaping moral core for its people. The Bushido code of the samurai is an excellent one. It has grit and backbone, but so far has been difficult for them to relate to outside of it feudalist context, though it’s rich material to work with. Zatoichi is so upbeat and loveable, despite the pathos he witnesses. He goes against the grain.

What sort of meta-narrative lens will emerge to help them process the 3/11 earthquake-tsunami-nuclear triple disaster? If there’s any conclusion to be drawn from this, perhaps it is that the serial stagnation of giant rubber suit monster and robot stories – while fun at times – will do nothing to give Japan a deep and unifying sense of national destiny. On an individual level for a collectivist society, the disintegration of the family unit and absentee fathers remains the fundamental problem. America suffers from a similar attack but does not seem to feel it as acutely due to its fixation on rugged militaristic individualism. After all, the very war that made Japan feel the emptiness of itself was the war that set America up as a superpower, fighting as we did on foreign soil.

It’s harder to see the problems in one’s own culture sometimes. America is still somewhat of an adolescent in world history. Except for the War Between the States, we have little sense in our national memory of devastation like Dresden and Hiroshima. The rest of the world has seen their homelands ravaged time and again by war.

On one level, of course, I know that Jesus, Lord of Heaven and Earth, is the only real answer to any society’s problems, because the root of all problems lies with sin, which is our fundamental estrangement from relationship with our Creator. There is no vertical sense of ultimate relationship to be found in Japanese culture – for centuries it has been systematically suppressed and stamped out by the government. However, there can be no substitute for spiritual hierarchy and no zaibatsu can provide existential purpose to its employees.

On another level, a worldview of pacifism, compulsive dependency (amae), and worshipping at the altar of corporate culture has only led to a laissez-faire outlook on life, family, and parenting.

|

| Japan's nuclear family? (Dad not pictured; at work) |

We need banners that are worthy of our swords, and our priorities must be as unyielding as the samurai spirit, devoted to one another. It’s fine to borrow yesterday’s imagery, but there also needs to be new stories and to uncover inspiring national heroes, ones with which Japan can regain an emergent sense of hope.

Perhaps Ultraman could be re-invented to be more grounded and to fight threats that hit closer to home. First thing though, he’d have to be given speech. Have you noticed he never talks? Now tell me how you can have anything more than a 2D character without words? Or go back to kamishibai superheroes like Takeo Nagamatsu’s 1931 the Golden Bat - if he wasn’t such a knock-off of the Phantom of the Opera. If modern day manga and gekiga writers and filmmakers could tone down the blend of silliness and eroticism and actually give due justice and gravitas to folk heroes like Kintarō, Momotarō, or Tawara Tōda, or historical figures like Prince Yamato-Dake, Kirigakure Saizō, Abe no Seimei, Goemon Ishikawa, Tomoe Gozen, Benkei, Miyamoto Musashi, Amakusa Shiro, or Saigō Takamori - in all likelihood there already are some good treatments out there; there just needs to be a good PR push with a tie-in to current issues. One could splice in some elements from inspirational anime characters like Captain Harlock or Joe Yabuki. Or, hey, just start translating over some Usagi Yojimbo.

It is unfortunate that Japan can't simply drape a flag around a guy, slap on some kabuki make-up, and call him Captain Japan (Nippon Man? Sunfire? Oh, wait, copyright laws…). Over in England, Captain Britain and Union Jack both have great costumes, but the moral integrity of our beloved Cap is something to behold – he is worthy enough to heft Mjolnir after all.

|

| Jan-ken-POI!!! |

He has no superpower to speak of, but his tactical skills and determination that make him one of the best fighters in the Marvel Universe – able to take down the Hulk if need be. He is also unabashedly moral, which at times might seem old-fashioned to those around him, but as a father figure it works perfectly.

There’s a nice scene in the movie that mentions this:

Captain America [feeling out of place]: The uniform? Aren’t the stars and stripes a little... old-fashioned?

Agent Coulson: 'Everything that’s happening… with things that are about to come to light… people might just need a little ‘old fashion’.

He is the superhero’s superhero, the inspiration for Spider-Man and natural choice of leader to unify any team. Finally, the shield is the perfect weapon for a hero who is the image of restraint, defense, and reason.

|

| Sneak attack from behind? Cheap shot there, Tojo... |

The hero’s powers might be connected to nature, such as Mt. Fuji or the sun, but without resorting to out-and-out environmental messaging. Sunfire of Marvel Comics gets his powers from solar radiation; not a bad idea, but as far as personality goes, he's kind of a jerk and not a team player. Japan's newest ninja-cunning, monster-slaying, nation-inspiring heroes have to have the mettle to transcend the silliness of fads and endure to become modern legends.

Okay, there are some raw ideas for you Japan. We're with you. Now show us what you’ve got.

________________________________

1 When I was in elementary school – around the time I was filming those toy Godzilla movies – we still had air-raid sirens go off every Friday, but I was too young to understand the threat of the Soviets. I was too busy watching the overflow of patriotic sci-fi cartoons like Bravestarr, G.I. Joe: “A Real American Hero”, Transformers, and Starcom: The U.S. Space Force, not to mention playing with all those action figures.

2 Instead of suffering the fate of Hitler and Mussolini, Hirohito was merely demoted. Indeed, the official cover story perpetuated by the Occupation was that he was basically duped by the Japanese army and was more or less in the dark about many of the decisions during the war. It was an extremely generous amount of face-saving given by the Americans.

Unfortunately, it wasn’t true, and the unresolved complications of this matter of Japan’s culpability in war crimes have led to the continued problems today with its neighbors. Had Hirohito been executed or jailed, I wonder if the rest of East Asia might not find it sufficient justice, the same way Germany has emerged from its role in history with a new beginning. With all the denials and revisionism and ultra-nationalist gaisensha (街宣車) vans still roaming Japanese public discourse, many today still doubt the sincerity of such repentance. Even worse, the ramifications of this American whitewashing meant that the Japanese people were led to think their government was largely innocent, with General Tōjō and his ilk bearing the majority of the blame.

3 See William Woodard, The Allied Occupation of Japan 1945-1952 and Japanese Religions (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1972), p. 243, 245, 273.

4 Church and State, Vol. 17, No. 6, June 1964, p. 10.